Flying high in Switzerland:

A journey into space

The fantastic journey begins at the University of Bern. Students sit outside, professors and postgraduates stroll past the main building in the mild October air. It’s a beautiful day in Switzerland and the large, yellow sun shines as if it were the only star in the universe.

A glass door in the Physics Institute leads to the department for Space Research and Planetary Sciences. Welcome to the Center for Space and Habitability.

Posters of rockets and UFOs decorate the lobby. Satellites buzz around purple moons and small figures with antennas on their heads march across crater landscapes. But the questions the posters raise are serious. Is there a second Earth? Are there planets out there made of more than gases and mud, and might they have an atmosphere?

In Switzerland, space researchers are addressing such questions with scientific rigour and precision. So, anyone who mainly associates the small, mountainous country mainly with cheese, cows and expensive watches should think again!

Back in the 1960s, Bern University developed the solar sail for the Apollo mission right here in the Physics Institute, contributing to the moon landing. Many Bern-made instruments and measuring devices are circling in orbit or racing through our solar system with a space probe. In 1995, two Swiss astronomers also detected the first exoplanet – the discovery of 51 Pegasi b is regarded as an astronomical milestone.

Bern-built mass spectrometers have flown to distant comets to analyse their atmosphere. Other instruments from the Bern lab have flown to Jupiter and the Sun. Scan the list of space missions the Swiss have been involved in and you’ll almost leave the ground yourself.

They’ve been to Mars and to Venus, have analysed space plasmas. Space probes have ventured all the way to Jupiter’s icy moons with Bern’s precision instruments on board – to search for traces of life in the deep oceans of Ganymede, Kallisto and Europa.

The questions are big ones. How did the universe come into being? How did life on Earth arise? A fascinating journey. And definitely the most daring one we earthlings have ever participated in.

The current research programme is called PlanetS. Its purpose is to discover what planets are composed of and whether life could exist there. In order to find out, astronomers are gathering rock samples and data from distant asteroids, comets and meteorites. Do any of these distant objects have a biosignature? If so, what is it?

Nikita Boeren and Peter Keresztes Schmidt are at the Institute of Exact Science this morning. The doctoral students of physics and astrochemistry occupy themselves full-time with the stars, and are as familiar with the basics of astronomy as others are with the price of butter at the supermarket. They’re also following a long tradition, as no lesser man than Albert Einstein once lectured at this university.

Einstein spent his ‘happy Bernese years’ in Switzerland from 1902 to 1909. In the miracle year of 1905, also in Bern, he developed his theory of relativity. As a professor, he began teaching here in 1908. His first class started at 7 a.m. and was entitled ‘Molecular Theory of Heat’. Three students initially attended his lectures, but soon their number dwindled down to one. Einstein was no pop star of physics in those days, but rather an eccentric who drew funny circles on the chalkboard.

Today, an elevator takes the young astronomers up to the first floor. ‘Welcome to our office’, says Peter Keresztes Schmidt. Delicate milling cutters, pliers, tweezers lie scattered on the tables. Behind curtains, there’s a clean room with a silvery unit and across from it, a microbiological safety workbench. Instruments for future space flights are built in this Swiss space lab.

Gold-plated mass spectrometers will accompany a NASA mission to the moon in a few years. Once there, a laser beam will pulverise rock samples, after which the ionised fragments will be separated in the spectrometer according to their atomic mass so that researchers can determine the chemical composition of the rock. Keresztes Schmidt explains: ‘This method allows us to determine on site which elements are present. Aluminium, iron, perhaps other substances as well. It’s important to know in case we want to establish a presence on the moon.’

A presence?

‘Yes, a space station, for instance, from which to travel on to Mars.’

After lunch we are joined by Martin Rubin. The planetary scientist and comet expert was involved with the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission in which mass spectrometers and pressure sensors orbited the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. The Swiss precision sensors on board the space probe were meant to analyse the gases and ice particles the comet released so as to unravel the mystery of how planets are formed.

Rubin says: ‘The comet is 4.5 billion years old, but its hydrogen and helium molecules date back to the Big Bang, which took place 13.8 billion years ago. Comets are witnesses to the history of the formation of our solar system.’

This begs the mother of all questions. What came before the Big Bang? Martin Rubin, in sneakers and a blue sweatshirt, says: ‘We don’t know. And we’re unable to imagine it. Before that, there was no space and, consequently, no time. Before the Big Bang, there was the opposite of eternity, so to speak.’

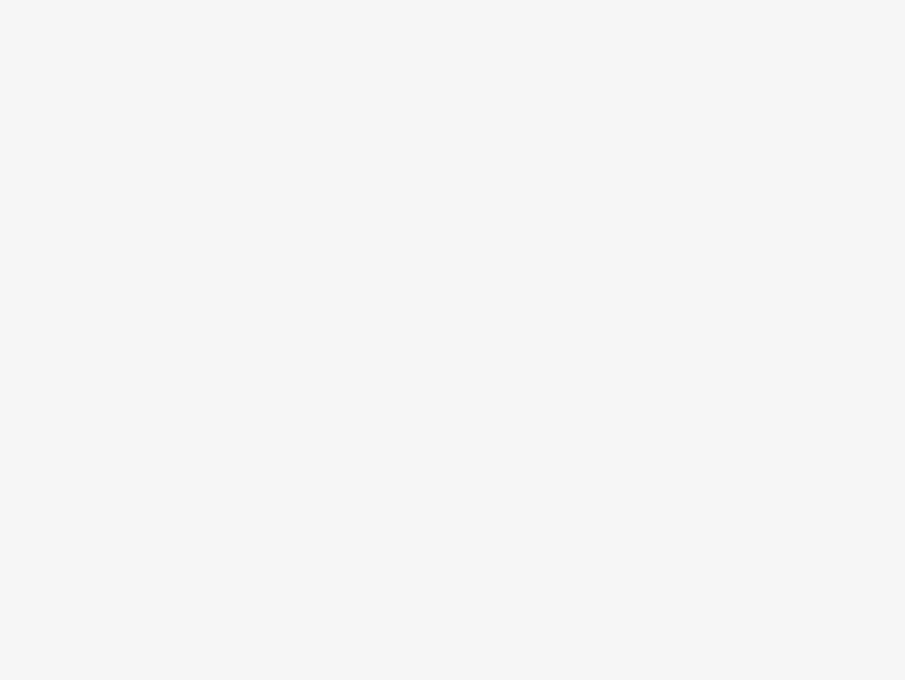

Rubin also builds instruments that will accompany probes and satellites into the cosmic vacuum. Everywhere you look, apparatus, encased cylinders. The jumble of technical gear would have astounded even Gyro Gearloose. Rubin points to one of the devices and explains: ‘This time-of-flight mass spectrometer will fly to a comet in 2029 to answer further questions.’

Mais la Suisse s’ouvre à des horizons encore plus lointains : aux confins de l’espace et du temps. Pour apercevoir de telles perspectives intergalactiques, direction Zermatt. Cette ville alpine est un véritable havre de paix pour les visiteurs. Au village, crêperies, bars, boutiques et restaurants chics abondent. Tout là-haut, la star de la région règne en maître : le Cervin, une pyramide enneigée s’élevant verticalement vers le ciel.

Le deuxième plus haut chemin de fer à crémaillère à ciel ouvert d’Europe part de la station inférieure et effectue son ascension en direction de Gornergrat. La limite forestière approche, les névés défilent, puis il s’arrête : nous avons atteint 3.100 mètres d’altitude.

Tout autour se dressent des sommets de quatre mille mètres. Mais ce n’est pas tout : c’est aussi là que se trouve l’hôtel le plus haut de Suisse.

Le Kulmhotel Gornergart ressemble à un château fort flottant au-dessus des nuages. À l’intérieur, 22 chambres à la douce odeur de bois de pin, des salles de bains modernes et du linge de lit d’un blanc immaculé. Au rez-de-chaussée deux restaurants où sont exposées des œuvres d’art moderne et proposant des menus raffinés. Mais cet hôtel est bien plus qu’un simple hôtel, il abrite également le Stellarium Bornergrat, un observatoire d’où l’on peut observer les confins de l’univers.

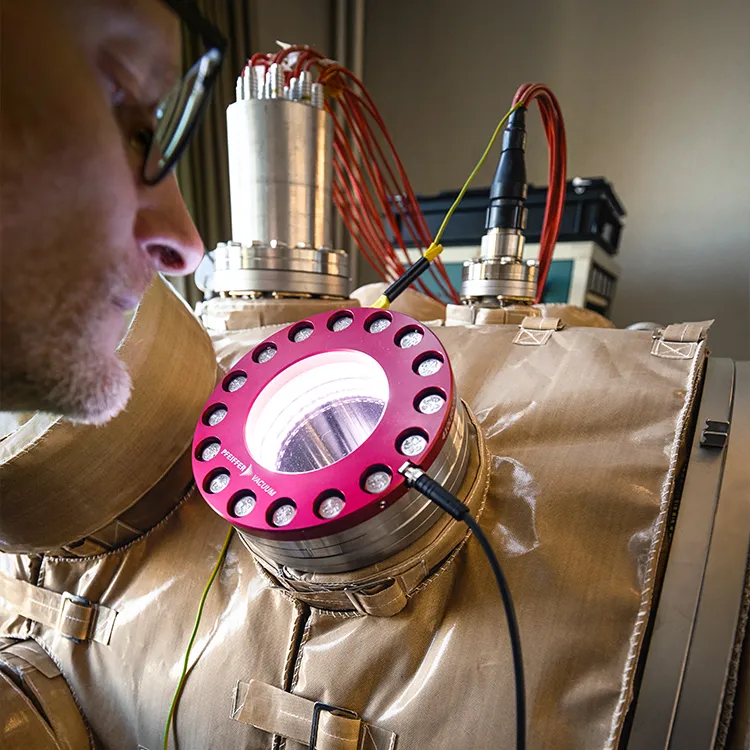

Le directeur de l’observatoire est Timm Riesen, docteur en astrophysique et expert en spectrométrie de masse, galaxies et nébuleuses cosmiques. Il a passé six ans à Hawaï pour le compte de la NASA et était présent au lancement de la fusée Ariane 5 en Guyane française.

Il monte au sommet de la tour nord de l’hôtel. Ici, sous une grande coupole, se trouve « l’œil », le télescope. Timm Riesen ajoute : « La caméra Deep Sky nous permet d’observer l’univers jusqu’à 100 millions d’années-lumière de profondeur, prendre des photos d’amas de galaxies, d’étoiles binaires et de nébuleuses spirales lointaines. »

Timm Riesen pivote le télescope et les portes s’ouvrent. Derrière, on aperçoit un ciel nocturne glacial et des étoiles qui brillent. Certains phénomènes sont clairement visibles à travers l’oculaire de l’appareil. Les vrais mystères cependant sont révélés sur les écrans de l’ordinateur.

Il montre la nébuleuse d’Andromède. « Notre voisine dans l’espace », dit-il. « Une galaxie spirale située à 2,5 millions d’années-lumière. » Puis de nombreuses autres formations stellaires apparaissent sous la forme de motifs et constellations insolites. La nébuleuse de l’Aigle, la nébuleuse de l’Haltère, la galaxie du Tourbillon, l’amas de la Vierge. Timm Riesen ajoute : « Bien que tous se situent à 54 millions d’années-lumière, nous en faisons partie. »

Il fait un froid glacial sous la coupole du télescope. Au-dessus, la Voie lactée brille de mille feux. Timm Riesen poursuit son exposé. Selon les dernières découvertes, les chercheurs estiment qu’il y a quelque 200 milliards de galaxies rien que dans l’univers visible. Un chiffre qui dépasse l’imagination. Mais il y a encore mieux.

À la question de savoir s’il existe d’autres formes de vie, Timm Riesen répond : « Nous avons déjà découvert 5.000 exoplanètes. Selon des calculs récents, il doit existent entre 200 et 400 milliards d’étoiles comme le Soleil, autour desquelles gravitent autant de planètes. Les perspectives sont donc bonnes. »

De quelles perspectives parlez-vous ?

Timm Riesen précise : « De la probabilité qu’il existe d’autres formes de vie, qu’elles soient unicellulaires ou avec un peu de chance multicellulaires comme chez nous sur Terre. »

Auteur

Photographe

Aluminium Collection

Alliée de voyage

Parcourez le monde avec nous