An elevating experience:

See the Alps from a hot-air balloon

The transport vehicle: a gigantic balloon filled with nothing but hot air and driven only by the wind. It’s the oldest means of air transport in human history.

The guests have a general idea of what lies ahead. After all, they received a short briefing and the internet is full of photos and reports. But nobody knows exactly what it will feel like to be high in the sky in a hot-air balloon. To stand in a rattan basket, breathing oxygen, icy air at your feet and thousands of metres between you and the abyss.

The transport vehicle: a gigantic balloon filled with nothing but hot air and driven only by the wind. It’s the oldest means of air transport in human history.

The guests have a general idea of what lies ahead. After all, they received a short briefing and the internet is full of photos and reports. But nobody knows exactly what it will feel like to be high in the sky in a hot-air balloon. To stand in a rattan basket, breathing oxygen, icy air at your feet and thousands of metres between you and the abyss.

At the airfield, the gondolas are unloaded and a propane-fuelled burner sends hot air into the colourful envelopes. Very soon, they stand upright over the apron like gigantic airbags. Striding past the heavy bags, fans and lengths of line, Peter Flaggl prepares for take-off. The experienced pilot has 7,000 balloon flights under his belt. Dressed in leather boots and a blue anorak, he says: ‘Our balloon holds 9,200 cubic metres of air. That’s equivalent to 9.2 million litres of beer.’

Flaggl is the son of an experienced balloonist and a veteran of the air. He was only five when he first climbed into a rattan basket and sailed silently aloft. Flaggl thoroughly enjoys this type of air travel, particularly across the Alps.

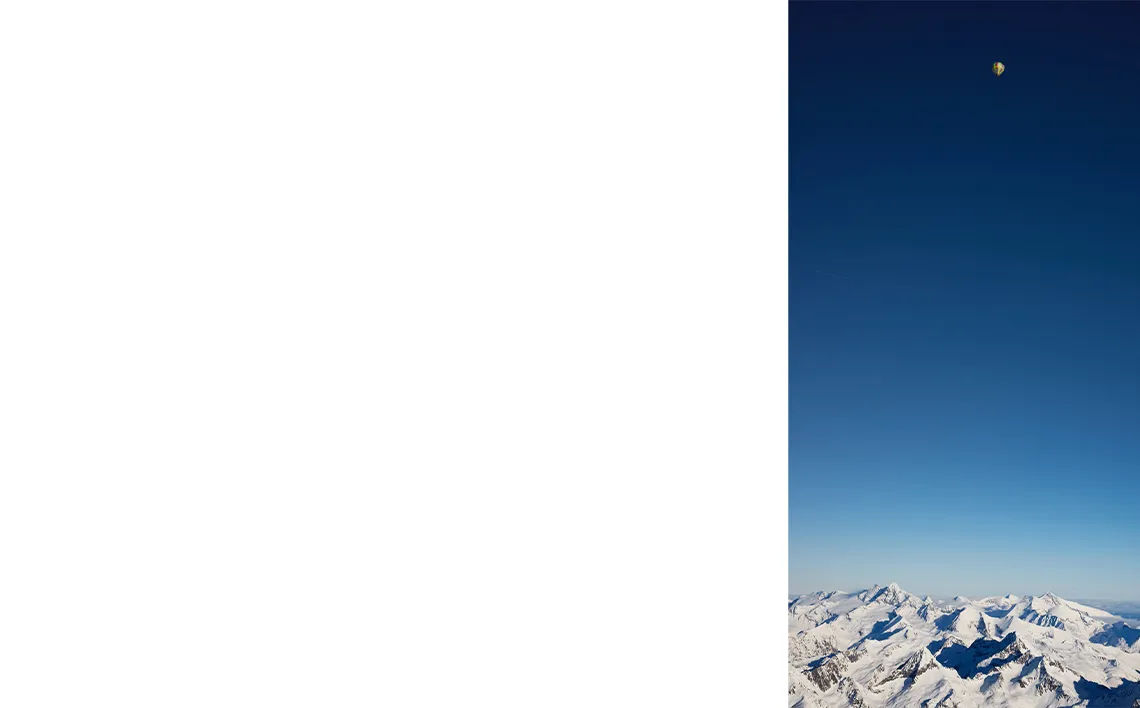

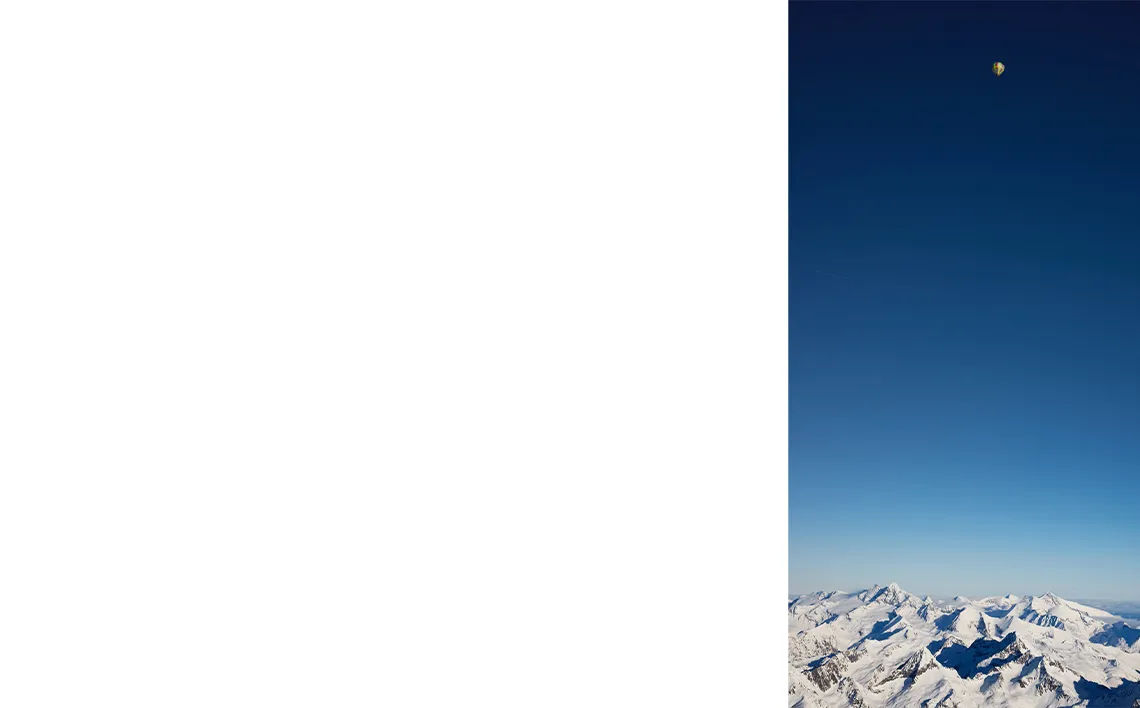

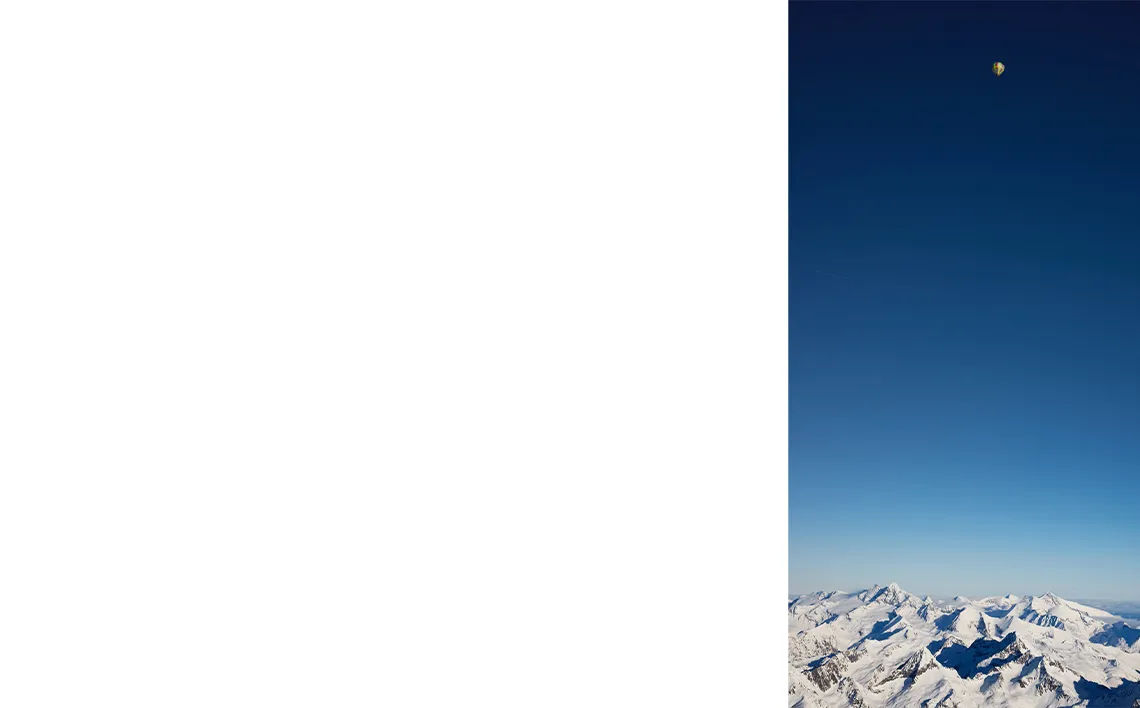

Nobody knows exactly how long the journey will take. Once the balloons leave the ground, they can no longer be steered, but drift with the currents and become one with the wind. All you can adjust are the rates of climb and descent when the craft is in the air, floating off into the blue. The wind plays a crucial role. At over 5,000 metres, the balloon glides through the air completely disconnected from the ground. To float in humanity’s oldest aircraft is like drifting on an atmospheric whim.

At the airfield, the gondolas are unloaded and a propane-fuelled burner sends hot air into the colourful envelopes. Very soon, they stand upright over the apron like gigantic airbags. Striding past the heavy bags, fans and lengths of line, Peter Flaggl prepares for take-off. The experienced pilot has 7,000 balloon flights under his belt. Dressed in leather boots and a blue anorak, he says: ‘Our balloon holds 9,200 cubic metres of air. That’s equivalent to 9.2 million litres of beer.’

Flaggl is the son of an experienced balloonist and a veteran of the air. He was only five when he first climbed into a rattan basket and sailed silently aloft. Flaggl thoroughly enjoys this type of air travel, particularly across the Alps.

Nobody knows exactly how long the journey will take. Once the balloons leave the ground, they can no longer be steered, but drift with the currents and become one with the wind. All you can adjust are the rates of climb and descent when the craft is in the air, floating off into the blue. The wind plays a crucial role. At over 5,000 metres, the balloon glides through the air completely disconnected from the ground. To float in humanity’s oldest aircraft is like drifting on an atmospheric whim.

The principle couldn’t be simpler. Hot air has more kinetic energy and thus a lower density than cold air. It’s lighter, so it wants to rise. If this force is greater than the weight of the vehicle plus its occupants, a miracle occurs: the balloon leaves the ground.

At half past nine the passengers climb into the gondola. There are eight of us standing in small compartments open to the air. Above our heads, a giant dome filled with air. On the left in the gondola, Flaggl moves a lever to operate the burner. A column of hot air hisses skyward, heating the interior of the envelope to between 80 and 120 degrees.

On the apron, someone from the ground team untethers the last line. The gondola begins to move, pushing a bit of snow in its path. Leaving the earth behind, we begin silently floating upward. The airfield falls away below us. The village of Zell am See grows smaller, the houses, the church, the streets – all lose scale.

The principle couldn’t be simpler. Hot air has more kinetic energy and thus a lower density than cold air. It’s lighter, so it wants to rise. If this force is greater than the weight of the vehicle plus its occupants, a miracle occurs: the balloon leaves the ground.

At half past nine the passengers climb into the gondola. There are eight of us standing in small compartments open to the air. Above our heads, a giant dome filled with air. On the left in the gondola, Flaggl moves a lever to operate the burner. A column of hot air hisses skyward, heating the interior of the envelope to between 80 and 120 degrees.

On the apron, someone from the ground team untethers the last line. The gondola begins to move, pushing a bit of snow in its path. Leaving the earth behind, we begin silently floating upward. The airfield falls away below us. The village of Zell am See grows smaller, the houses, the church, the streets – all lose scale.

The principle couldn’t be simpler. Hot air has more kinetic energy and thus a lower density than cold air. It’s lighter, so it wants to rise. If this force is greater than the weight of the vehicle plus its occupants, a miracle occurs: the balloon leaves the ground.

At half past nine the passengers climb into the gondola. There are eight of us standing in small compartments open to the air. Above our heads, a giant dome filled with air. On the left in the gondola, Flaggl moves a lever to operate the burner. A column of hot air hisses skyward, heating the interior of the envelope to between 80 and 120 degrees.

On the apron, someone from the ground team untethers the last line. The gondola begins to move, pushing a bit of snow in its path. Leaving the earth behind, we begin silently floating upward. The airfield falls away below us. The village of Zell am See grows smaller, the houses, the church, the streets – all lose scale.

Wir fliegen bald über den Großglockner, den höchsten Berg Österreichs. Längst müssten wir weit über 4.000 Meter hoch sein. „Stimmt“, sagt Flaggl. „Aber wir fliegen nicht, wir fahren! Sag im Ballon niemals fliegen, sonst musst du unten eine Runde Schnaps ausgeben.“

Der mächtige Berg kommt näher. Von oben betrachtet ein zerfurchter Kreis mit ausladender Schürze. Die Flanken weiß ziseliert. Alles karg und kalt. Eine gefrorene Schönheit. Der Ausblick ist jetzt maximal umwerfend. Deutschland im weiten Norden. Österreich rundherum. Im Westen die Schweiz, im Süden Italien, Slowenien.

Und: Mucksmäuschenstill ist es hier oben. Ein leiser Wind streicht um die Gondel, ansonsten scheint die Luft zu stehen. Nichts regt sich. Da wir mit der Strömung fahren, weht uns nichts entgegen. Kein Fahrtwind, null Gegenwind. Wir sind Teil des atmosphärischen Flusses geworden, segeln widerstandslos mit den Gezeiten der Troposphäre.

Keine Frage: Dies ist die abgehobenste Aussichtsplattform der Welt. Keine Kanzel, keine Scheibe trennt dich von den Elementen. Du spazierst hier oben durch den Himmel, fährst mit 100 Kilometern pro Stunde über alle Berge – und könnest gemütlich Zeitung lesen.

Wir fliegen bald über den Großglockner, den höchsten Berg Österreichs. Längst müssten wir weit über 4.000 Meter hoch sein. „Stimmt“, sagt Flaggl. „Aber wir fliegen nicht, wir fahren! Sag im Ballon niemals fliegen, sonst musst du unten eine Runde Schnaps ausgeben.“

Der mächtige Berg kommt näher. Von oben betrachtet ein zerfurchter Kreis mit ausladender Schürze. Die Flanken weiß ziseliert. Alles karg und kalt. Eine gefrorene Schönheit. Der Ausblick ist jetzt maximal umwerfend. Deutschland im weiten Norden. Österreich rundherum. Im Westen die Schweiz, im Süden Italien, Slowenien.

Und: Mucksmäuschenstill ist es hier oben. Ein leiser Wind streicht um die Gondel, ansonsten scheint die Luft zu stehen. Nichts regt sich. Da wir mit der Strömung fahren, weht uns nichts entgegen. Kein Fahrtwind, null Gegenwind. Wir sind Teil des atmosphärischen Flusses geworden, segeln widerstandslos mit den Gezeiten der Troposphäre.

Keine Frage: Dies ist die abgehobenste Aussichtsplattform der Welt. Keine Kanzel, keine Scheibe trennt dich von den Elementen. Du spazierst hier oben durch den Himmel, fährst mit 100 Kilometern pro Stunde über alle Berge – und könnest gemütlich Zeitung lesen.

Wir fliegen bald über den Großglockner, den höchsten Berg Österreichs. Längst müssten wir weit über 4.000 Meter hoch sein. „Stimmt“, sagt Flaggl. „Aber wir fliegen nicht, wir fahren! Sag im Ballon niemals fliegen, sonst musst du unten eine Runde Schnaps ausgeben.“

Der mächtige Berg kommt näher. Von oben betrachtet ein zerfurchter Kreis mit ausladender Schürze. Die Flanken weiß ziseliert. Alles karg und kalt. Eine gefrorene Schönheit. Der Ausblick ist jetzt maximal umwerfend. Deutschland im weiten Norden. Österreich rundherum. Im Westen die Schweiz, im Süden Italien, Slowenien.

Und: Mucksmäuschenstill ist es hier oben. Ein leiser Wind streicht um die Gondel, ansonsten scheint die Luft zu stehen. Nichts regt sich. Da wir mit der Strömung fahren, weht uns nichts entgegen. Kein Fahrtwind, null Gegenwind. Wir sind Teil des atmosphärischen Flusses geworden, segeln widerstandslos mit den Gezeiten der Troposphäre.

Keine Frage: Dies ist die abgehobenste Aussichtsplattform der Welt. Keine Kanzel, keine Scheibe trennt dich von den Elementen. Du spazierst hier oben durch den Himmel, fährst mit 100 Kilometern pro Stunde über alle Berge – und könnest gemütlich Zeitung lesen.

Wir gleiten weiter gen Süden, grenzenlos, schwerelos. Flaggl schaut auf den Höhenmesser und verkündet: „5.521 Meter.“ Eine überaus ansehnliche Flughöhe – im Wortsinn. Im Süden ist erstmals das Mittelmeer zu sehen, derweil wir gerade die Ausläufer der Dolomiten passieren, Cortina d’Ampezzo im Westen, im Osten der Monte Zoncolan und das Spielzeugörtchen Tolmezzo. Im Süden: Triest, rechts unten die Lagunen und Buchten Venedigs.

Es ist, als glitten wir über eine Landkarte. Über die Schraffuren eines überdimensionierten Weltatlas. Dahinter beginnt eine endlose Fläche, die sich wie Silberpapier ausbreitet. Die Adria, das Mittelmeer. Es bleibt nur ein Wort: gewaltig.

Fast vier Stunden sind wir in der Luft, die Füße Eiszapfen, als nun der Sinkflug ansteht. Flaggl zieht eine Leine, öffnet den Parachute, eine Klappe oben in der Ballonhülle, aus der die heiße Luft entweicht. Wir sinken, behutsam wie in einem Fahrstuhl.

Die italienische Ebene zeichnet sich ab. Eine braune Platte, dekoriert mit immer mehr Details. Flaggl von links: „2.000 Meter, weiter sinkend.“ Es folgt der heikelste Teil der Reise. Die Erde kommt näher. Unten sind wieder Autos zu erkennen, Lastwagen, Straßen. Und auch das: Überall stehen Telefonmasten und Stromleitungen in der Gegend herum – die wir dringend meiden müssen!

Das Landemanöver erfordert viel Gefühl. Als müsse man mit einem im Wind tanzenden Luftballon eine Punktlandung hinbekommen. Flaggl: „Man braucht ein Händchen dafür. Manche Piloten lernen es schnell, andere nie.“ Der Ballon-Veteran bleibt seelenruhig. Er hat das schon 7.000-mal gemacht.

Ein brauner Acker kommt näher. Die Kufen setzen auf. Dann herrscht Stille. Ein warmer Wind geht. Wir sind in Italien – gelandet in einem Weizenfeld in der Nähe der kleinen Stadt Pordenone.

Schweigend krabbeln die Passagiere aus dem Korb und trauen ihren Augen nicht. Über das Feld stürmt ein Bauer und trägt zwei Flaschen Rotwein in Händen. Die Luft ist warm. Vögel zwitschern. Und dann wird erst mal ordentlich eingeschenkt. Ein ungeplanter Willkommenstrunk – mitten auf einem Acker, mitten in Italien. Nun, so ein wunderschöner großer Luftballon landet schließlich nicht alle Tage vor deiner Nase.

Autore

Fotografo

Aluminium Collection

Compagni di viaggio

Scopra il mondo con noi